| Submission Procedure |

A Collaborative Biomedical Research SystemAdel Taweel Alan Rector Jeremy Rogers Abstract: The convergence of need between improved clinical care and post genomics research presents a unique challenge to restructuring information flow so that it benefits both without compromising patient safety or confidentiality. The CLEF project aims to link-up heath care with bioinformatics to build a collaborative research platform that enables a more effective biomedical research. In that, it addresses various barriers and issues, including privacy both by policy and by technical means, towards establishing its eventual system. It makes extensive use of language technology for information extraction and presentation, and its shared repository is based around coherent "chronicles" of patients' histories that go beyond traditional health record structure. It makes use of a collaborative research workbench that encompasses several technologies and uses many tools providing a rich platform for clinical researcher. Keywords: cancer, computerized patient records, natural language processing, bioinformatics, privacy, confidentiality, security, electronic health records Category: K.6.5, J.3, I.2.7, I.5.0, I.7.0, H.3.1, H.3.3, H.3.4, H.3.5, H.5.2, K.4.1 1 IntroductionOur rapidly increasing ability to gather information at the molecular level has not been matched by improvements in our ability to gather information at the patient level. There is a strong convergence of need between current trends towards safer more evidence based patient care (e.g. [Kohn 2000]) and current trends in post-genomic research1 which seek to link molecular level processes to the progress of disease and the outcome of treatment . Both need to be able to answer the questions: What happened and why? What was done and why.

1research on genomics ? the study of genes and their functions- for translating the outcomes of the humane genome project into medical discoveries. Page 80 Simple though these questions may seem, they remain difficult to answer without recourse to manual examination of patients' notes ? a time consuming process whether the notes are electronic or paper. Yet without answers to these questions, it is difficult either to measure the quality of care or to investigate the factors affecting onset and recurrence of disease. The Clinical E-Sciences Framework (CLEF) project seeks to address key barriers to answering those questions. Its prime objective is to produce an end-to-end cycle that both improves information for patient care and results in a growing repository of pseudonymised patient data linked to genetic and genomic information that can be safely shared for biomedical research. The emerging design presents a vision of effective safe information management serving both patient care and biomedical research. However there are various barriers and issues that need to be removed or addressed before this can be accomplished. We categorise the key barriers and/or requirements as follows:

Initially, the project focuses on cancer as a pilot area, however it aims to provide a model that might be used in many disciplines. Cancer has the obvious advantages of immediate links to post-genomic research and overall importance in the strategy of the NHS and most other health systems. However, there are two less obvious features of cancer that make it a useful test case for prototype systems.

Various methods and technologies are used in the project to address these barriers, issues or requirements. The rest of the paper attempts to describe these methods and technologies in more details. Page 81 2 Information flowThe requirements and technologies are best understood in the context of the information flow that has emerged from the design process and is shown in Figure 1. Starting with the "Patient care and dictated text" at the top of the diagram, the flow is:

Page 82 Figure 1: Basic CLEF Information Flow From this point the information can go in two directions.

Another potential direction for the information flow is that the information can be further enriched by the results of researchers' queries, their workflows, interpretations, curation and links to external information and thus becomes the basis for virtual communities of researchers. Page 83 3 Methods and TechnologiesThe focus is on the specific technologies which are currently barriers to obtaining and integrating clinical information. The following describes the used methods and technologies to overcome the obstacles outlined above. It relates to each of the respective parts of the information flow diagram shown in Figure 1, except that of the privacy and confidentiality where it was set as a policy framework in the project that took a significant amount of effort and time to complete the process, which as a repercussion caused delays in the initial stages of the project. 3.1 Security, privacy, confidentiality, and consentAs it is clear from the "stop signs" in Figure 1, much of the infrastructure involves privacy and security. The overarching requirement is a policy and oversight framework for privacy and consent. No technical solution can be perfect, so confidence in the organizational measures is the most critical single criterion for success. Furthermore, no technical solution can succeed without vigilance. A key part of the policy is the obligation of care for all researchers to report potential hazards to privacy as part of the routine use of the repository coupled with technical measures to make it easy to do so. However, technical measures are required and the requirements potentially conflict. Pseudonymous identifiers must be secure but must also support a) linking from multiple sources, b) re-identification with consent by the healthcare provider c) withdrawal or modification of consent by the patient. Both initial pseudonymisation and re-identification must be done solely within the hospital providing the information. Therefore, two stages of pseudonymisation are at least envisaged: one for entry from the hospital level, a second for linkage and use within the repository itself. Combinations of trusted third parties and techniques from e-commerce (e.g. [Zhang 2000]) are being investigated. The project will eventually modify or develop it own algorithms suitable to the structure of the input data. Currently, to facilitate a fast transfer of raw data to the rest of the project, a non-sophisticated algorithm is used to pseudonymise the data at the hospital or data source. It removes mainly the patient identifying fields from patients records. This has been developed by the hospital to "fit" with the structure of its data and the deployed electronic record system. The use of text extraction requires that special attention be paid to removing identifiers from text using language technology — a process we term "depersonalisation" which uses well established techniques from "named entity extraction" [Gaizauskas 2003b] and related techniques [Taira 2002]. At the first stage, the corpus of records from deceased patients is used to check the effectiveness of the depersonalisation mechanisms, as a condition before using the records of live patients. A preliminary progress has been in the project towards this goal, however several formative implementations and evaluations of the natural language based technique are yet to be done. [Gaizauskas 2003b] provides further details. Page 84 The other side of the issue is the employment of statistical disclosure control technology (as a privacy enhancing technique) [Elliot 2002] to monitor and blur the output of queries to reduce the risk of deliberate or accidental re-identification through queries of the pseudonymised repository. No matter how well pseudonymised, de-identified and depersonalised, there is always a risk that personal data can be re-identified through sophisticated cross referencing, statistical or data mining techniques. This risk of such re-identification is well established and techniques to combat it are developing rapidly [Elliot 2002, Lin 2002, Murphy 2002, Sweeney 2002]. This technology focuses heavily on the assessment of risk in single, static and cross-sectional datasets [Cox 2001, Domingo-Ferrer 2001]. A systematic risk assessment disclosure control methodology [Cox 2001] for the additional risks posed by multiple table releases will be employed to further to reduce the risk of re-identification. Privacy is relative to risk and consent. All records in the repository contain detailed metadata on the level of consent granted for their use by patients. In fact, the project is significantly contributing to the existing efforts on creating agreed standards for metadata on consent within the community. See [Kalra 2003] a more detailed description of the privacy, confidentiality and security framework. 3.2 Information Extraction & Language TechnologyDoctors dictate. Much of the key information in clinical records continues, and will continue for the foreseeable future, to be contained in unstructured or at best minimally structured texts. Hence a major part of CLEF is devoted to adapting and evaluating mechanisms for information extraction from text [Gaizauskas 1996, Friedman 2002]. Four features of the cancer domain make information extraction feasible: a) the very limited sublanguage, even more so than for medicine as a whole [Friedman 2002]; b) much of the specialised information is in common with molecular biology which is a major target for current text extraction efforts e.g. [Swanson 1997, Gaiszauskas 2003b]; c) the well defined list of index events and signs that allows the template for extraction to be well defined; d) the existence of multiple reports for most events. The existence of multiple reports is particularly important and has not been widely noted elsewhere to the best of our knowledge. Cancer patients are seen over a long period of time and their records summarized repeatedly so that there are many parallel or near parallel texts — often 150 or more text documents per patient. What may be unclear or ambiguous in one text can be refined from others. This is particularly important when dealing with records from a referral hospital where the system will usually start in the "middle of the story". For example, first document might simply mention breast cancer in the past, concentrating on the current recurrence. A summary, later, might give a date for a mastectomy but no details of the tumour type. Page 85 Eventually, perhaps after information from the referring hospital was received, a definitive statement of the time, tumour, spread, and treatment might be found. A more detailed description of the information extraction process can be found in [Gaizauskas 2003a]. 3.3 "Chronicalisation", Repository and IntegrationAt the heart of architecture is the central EHR repository and "chronicle". The need for creating the "chronicle" came out of the classic problem of electronic health records, i.e. to maintain a faithful, secure, non-repudiatable record of what healthcare workers have heard, seen thought and done [Rector 1995]. The EHR repository follows standards designed to achieve these aims — e.g. OpenEHR [Ingram 1995], CEN standard 13606 [CEN/TC 2003], and associated development of "archetypes"[Beale 2002]. However, the central issue for this research is different to infer a single coherent view of each patients' history from the myriad documents and data in the EHR and to align them with other similar patients in aggregates for querying and research. Furthermore, our interest is not only in the literal information in the documents but in their clinical significance not only what was done but why. It is not enough to know that the report of a bone scan claimed "only osteoporotic changes". It is necessary to recognise that this indicates that there are "no bony metastases found". It is not enough to know that the patient was taken off chemotherapy, it is important to know what side effect or concurrent illness intervened. The compilation of a single coherent "chronicle" for each patient from distributed heterogeneous information that makes up the medical record is a major task. At one level, the chronicle provides a clear presentation to clinicians and researchers of the course of one patient's illness as shown in Figure 2. At another they are data structures which can be easily aligned on "index events" — diagnosis, first treatment, relapse, etc.- and aggregated for statistical analysis to answer questions such as "Of patients with breast cancer with a particular genetic profile, what is the comparison of the time to first recurrence for those treated with Tamoxifen as against those treated with a new proposed drug regimen". "How many dropped out of each treatment and why?" "How many required supplementary therapy for the side effects of treatment and why?" Assembling the chronicle is therefore a knowledge intensive task that relies on inferences. The reliability of these inferences may vary, and it is essential to record not only the inferences but also the evidence on which they were based and their reliability. A graphical presentation of a chronicle developed manually as part of the requirements exercise is shown in Figure 2. A human observer can quickly infer many of the reasons from the juxtaposition of events; an effective computer based "chronicle" must capture those inferences. The "chronicalisation" process employs several algorithms to draw different types of information or data and assemble its overall content into individual patient chronicle structures. Drawing up chronicle temporal information is one of the initial indexing algorithms, for example, which has partially been completed. The description of this algorithm is beyond the scope of this paper, please refer to [Harkema 2005] for further details. Page 86 Figure 2: An individual patient chronicle in graphical form 3.4 Collaborative WorkbenchFor the data in the repository to be useful, it must be easily accessible to scientists and clinicians. A common workbench (see Figure 3) is employed that acts as the outer layer, interface and/or window that enables end users and researchers to access, analyse and examine the underlying information. The workbench hides the complexities of the underlying technologies such as information extraction, repository etc. while providing the necessary mechanism to enable easy use of the technologies and information. It provides a coherent platform, with one "feel and look", allowing tools developed within the project or if appropriate in other projects to be plugged within the platform. The workbench is built around several open source technologies while allowing remote secure access to the CLEF authorised users. An application web server, such as Apache Jakarta Tomcat [Apache 2005], is used for delivering web content, on top of which a portlet container, such as Gridsphere [Novoty 2004], is used to unify the interface and presentation layer of the workbench. Page 87 Figure 3: CLEF Workbench Main Portal web Interface Several special technologies have been developed within the workbench including security, auditing, and logging, and tools for query formulation and visualisation and results presentation and summarisation. In addition, it includes tools that link to external available resources and relevant literature. The security components are built on technologies developed by other projects, such as Shibboleth and PERMIS [Chadwick 2003] for authentication and authorisation mechanisms, and use PKI infrastructure for secure encrypted transmission of data. Figure 4: CLEF workbench overall architecture The general CLEF architecture for the workbench framework is shown in (the overall diagram) Figure 4. In addition to others It highlights some of the (sub) components or services that the workbench framework includes and/or provides. Page 88 These briefly include: user and session management services, portal services, tools and users administration services, authentication and authorisation services, query formulation and visualization services, auditing and logging services, and relevant 3rd party services. Also other services such as hazard monitoring, statistical analysis are planned to be implemented or integrated at later stages. Figure 5: CLEF workbench (portal) architecture 3.4.1 The workbench architectureFigure 5 presents the CLEF workbench portal architecture. CLEF workbench consists of two main parts: the CLEF portal and the portlet container. The CLEF portal itself is made up of a collection of interface and service portlets classified, combined and structured to provide the main CLEF functions. The portlet container holds these portlets and other services, and is the main used underlying framework for integrating various CLEF (and 3rd party) components. The content delivery is done by the servlet-container Apache JakartaTomcat. The (end) user interface is provided by a single or combination of portlets, depending on the respective service or functionality. One of the main advantages of portlets is that they are able to handle rich visual interface controls, including direct mark up fragments, or those generated by a Java scripting language (JSP). Page 89 The underlying business logic is either implemented as service portlets (or servlets) within the workbench layer or aided by service portlets that communicate content from external services. Although there are limitations on the level of sophistication of user interfaces, especially graphical user interfaces, the workbench architecture has the flexibility of implementing the underlying business logic in various J2EE compliant technologies including EJB, or can potentially utilise WSRP to incorporate remote content and/or services. The workbench includes a service communication interface (or API) that communicates with external CLEF (local or remote) components, such as the knowledge base or the Information extraction components. It supports various communication mechanisms, including RMI and WSRP to support legacy components and web services respectively. The workbench framework is extensible to incorporate other 3rd party components, such as prolog, or database engines. The following sections describe the CLEF workbench services and components in more details. 3.4.2 The workbench structure and contentThe structure and the content are combined together to provide a coherent CLEF portal with one "feel and look" (see Figure 3). Because of the medical data sensitivity and CLEF security constraints, the content in the portal has been classified in three different general categories:

Page 90 The overall layout/structure of the CLEF portal has been designed based on these categories. These categories also defined the layout of each sub-part of the CLEF portal. Some areas of the portal are constraint by the provided end-user configurable layout or interface. Also content and services are sequenced (or put in workflows) differently and put in an optimal user interfaces and layout to achieve or perform a particular operation or unit-of-work, for different types of users (e.g. specialist clinical researchers, general users) depending on their privileges and type of function. 3.4.3 The workbench user and session management servicesAnother important feature of the workbench is that it has the capability to manage CLEF users. In addition to collecting demographic information, and establishing roles or privileges, which are then mainly used to authenticate users and set their authorisation levels, users must go through a registration and approval process before they are given access. Researchers must be accredited by the Ethical Oversight Committee to gain access through the workbench to anything except pre-computed results and metadata. Despite other precautions, it is assumed that if individual records can be read in detail, there is the risk of identification. Therefore, all information is treated with as if it were identifiable [Kalra 2003]. Most researchers will be accredited only for performing queries that generate aggregated results controlled through the disclosure control technologies. Special permission of the Ethical Oversight Committee is required to gain access to individual patient records even though they are pseudonymised. The user management in CLEF is not limited to the workbench, but also the whole system including the underlying data sources and services. Handling multi-user sessions simultaneously while keeping session instances separate across services and portlets is critical for the workbench. This is handled by the session manager. The following functions or services are provided by the user and session managers:

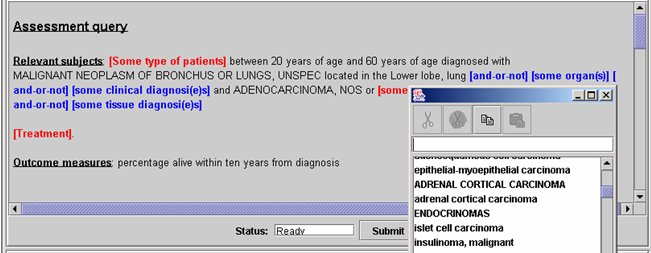

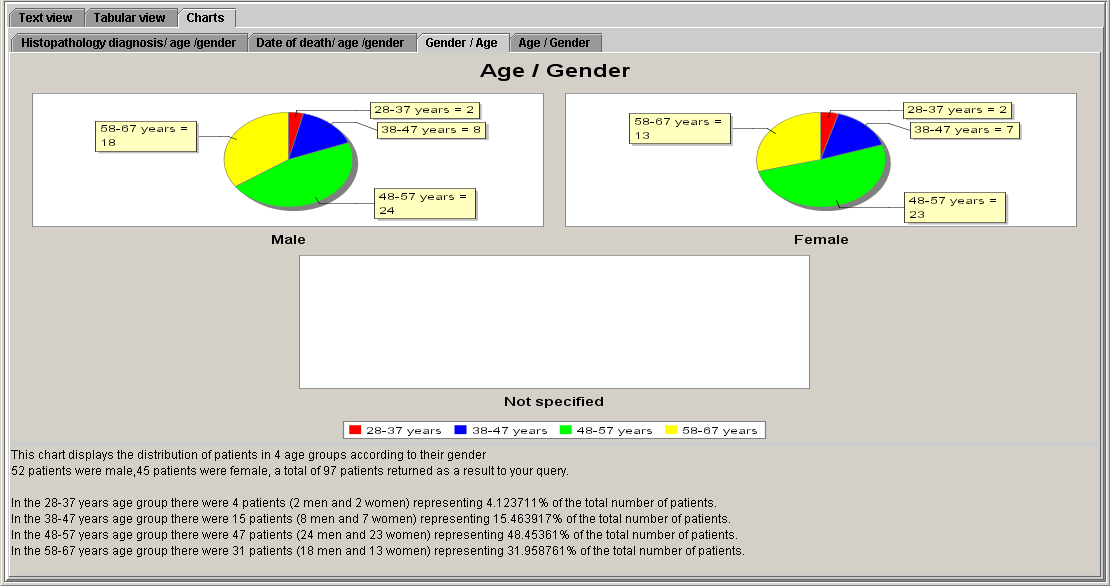

Page 91 3.4.4 The workbench query formulation and visualisation toolsThe other important part of the workbench is the query formulation and visualisation tools. We are experimenting with a variety of textual and graphical query and visualisation interfaces to the repository. However, the prime interface for researchers is being designed around techniques from language generation known as WYSIWYM "What you see is what you meant" [Power 1998, Bouayad-Agha 2000]. An example is given in Figure 6. The WYSIWYM interface allows users to expand a natural language like query progressively to produce queries of arbitrary complexity and then summarises the results, again in generated natural language. These interfaces are provided in different portlets and accessible by users depending on their access control privileges. They provide several types of queries and different ways of displaying results, e.g. graphical, textual, tabular etc. 3.4.5 The workbench Security and access controlThe security components of the workbench, i.e. authentication and authorisation are part of the overall CLEF security system. The authentication service enables registered to login in the workbench to access common general-user type information and services. The authorisation service determines access rights and privileges in terms of allowed services and related content. Users privileges are set and determined by the user registration and approval process including the intended purpose of using CLEF by the user. The description of CLEF security, ethical and confidential framework is beyond the scope of this paper. See [Kalra 2003] for further details. As mentioned above, CLEF security approach is built on technologies based on Shibboleth, FAME and PERMIS technologies. The workbench authentication is provided through Shibboleth and FAME with a single sign on (SSO) service integrated with the portal user interface. Authorisation is a role-based access control provided by PERMIS and governed by CLEF security policy. Their functionality and approach are described in more details in [Chadwick 2003]. Page 92 Figure 6: Example of WYSIWYM query formulation and result visualisation 3.4.6 The workbench information auditing/logging servicesAnother functionality of the workbench is storing information about various functional and user aspects, such as those related to user submitted queries, accessed information and services. Some of the stored information can be used by the SDC component, for instance to determine the output results of some of the submitted queries. The workbench information auditing component is linked to the data sources (knowledge base) information auditing components and the overall system provenance type information component. It audits/logs these three types of information, although the implementation is incrementally expanding to include finer details and potentially others. Page 93

3.5 Knowledge resources requiredAll the key technologies in CLEF are knowledge intensive. The overall approach is based on "ontology anchored knowledge bases" — knowledge bases anchored in common conceptual models but conveying additional domain knowledge about the concepts represented. Examples include which drugs are used for which purposes, the significance of different results from different studies, the fact that a seemingly positive finding such as "evidence only of degenerative changes" may in practice convey the negative information that "no metastases were found". Some of this information exists in established resources such as the UMLS [UMLS 2004]. However, most of it needs to be compiled. The repository is intended to be more than simply a data collection. Rather it is intended, in the spirit of "collections based research and e-Science" to be a repository of both data and what the interpretations of that data by various researchers, their conclusions, and the methods they have used to achieve them. In this, it requires intensive metadata of at least five types:

Page 94 The first three are shared much in common with clinical trials, and some of the metadata schemas must take into account the emerging standards for clinical trial metadata [CDISC 2004]. The fourth and fifth types of metadata are more specific to the biomedical and heath care focus. 4 Discussion and ConclusionThe convergence of need between post-genomic research and improved clinical care presents a unique opportunity; realising that opportunity suggests a radical restructuring of information flow and integration. The demand for large shared repositories of clinical and genomic information data is now clear. In the UK there are at least three other major initiatives: BioBank, the National Cancer Research Institutes/Department of Health National Translational Cancer Network, and the National Cancer Research Network [Biobank 2004]. Paradoxically, the genomic information is easy to capture. Although there will be increasing amounts of structured clinical data, experience suggests that much clinical information will continue to be dictated. Currently, this information can only be captured by labour intensive use of "data managers". Scaling this effort up manually is too resource intensive to be plausible. Fortunately, the many parallel texts and stereotyped course of cancer make it a particularly good area for information extraction. The sheer size, complexity, and repetition in cancer records make direct use of traditional electronic health records problematic and inefficient. Thus a coherent "chronicle" of patient histories is placed at the centre of the repository. The notion of "chronicle" owes much to ideas of "abstraction" developed in connection with guideline research [Rector 2001, Shahar 1997] and the notion of a "virtual patient record" in the HL7. The clear focus of the approach on "What was done and why?", "What happened and why" should contribute to these broader efforts as well as to its prime goal — to use clinical information intelligently and effectively for both patient care and post-genomic research. CLEF, through its workbench, developed technologies and underlying services, provides a coherent collaborative research environment that enables clinical and other researchers to safely and securely analyse, examine and query the underlying pseudonymised clinical information, drawn from operational electronic health records. The operational CLEF collaborative research system provides the infrastructure and tools and can be used by both, world wide by, remote authorised users and can be deployed in hospitals and used by in house clinicians to aid patient health care. Acknowledgments This research is supported in part by grant G0100852 from the UK Medical Research Council under the E-Science Initiative. Special thanks to its clinical collaborators at the Royal Marsden and Royal Free hospitals, to colleagues at the National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) and to our industrial supporters — see www.clinical-escience.org. Page 95 References[Apache 2005] http://jakarta.apache.org/tomcat/ [Beale 2002] Beale T. "Archetypes: Constraint-based domain models for future-proof information systems". In: OOPSLA-2002 Workshop on behavioural semantics; 2002; available from http://www.oceaninformatics.biz/publications/archetypes_new.pdf; 2002. [Biobank 2004] see http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/; http://www.ntrac.org.uk/; http://www.ncrn.org.uk/ [Bouayad-Agha 2000] Bouayad-Agha N, Scott D, Power R. "Integrating content and style in documents: a case study of patient information leaflets", Information Design Journal 2000;9(2-3):161-176. [CDISC 2004] e.g. see http://www.cdisc.org/; http://ncicb.nci.nih.gov/core [Chadwick 2003] Chadwick, D.W., A. Otenko, E.Ball. "Implementing Role Based Access Controls Using X.509 Attribute Certificates", IEEE Internet Computing, March-April 2003, pp. 62-69. [Cox 2001] Cox LH. "Disclosure Risk for Tabular Economic Data". In Confidentiality, Disclosure and Data Access (P. Doyle, J. Lane, J. Theeuwes and L Zayatz, eds) pp 167-183, 2001. Elseiver, Amsterdam. [CEN/TC 2003] http://www.chime.ucl.ac.uk/~rmhidsl/EHRcomMaterials.htm [Domingo-Ferrer 2001] Domingo-Ferrer J, Torra V. "A quantitative comparison of Disclosure Control methods for Microdata". In Confidentiality, Disclosure and Data Access (P. Doyle, J. Lane, J. Theeuwes and L Zayatz, eds) pp 111-133. 2001, Elseiver, Amsterdam. [Elliot 2002] Elliot MJ, Manning AM, Ford RW. "A computational algorithm for handling the special uniques problem". Int Journal of Uncertainty, Fuzziness and Knowledge Based Systems 2002;10 (5):493-511. [Friedman 2002] Friedman C, Kra P, Rzhetsky A. "Two biomedical sublanguages: a description based on the theories of Zellig Harris". Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2002;35(3):222-235. [Gaizauskas 1996] Gaizauskas R, Cunningham H, Wilks Y, Rogers P, Humphreys K. "GATE: An environment to support research and development in natural language engineering". In: Proceedings of the 8th IEEE International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence; 1996; Toulouse, France; 1996. p. 58-66. [Gaizauskas et al. 2003a] Rob Gaizauskas, Mark Hepple, Neil Davis, Yikun Guo, Henk Harkema, Angus Roberts, and Ian Roberts. "AMBIT: Acquiring medical and biological information from text", In S. Cox (ed), Proc. of UK e-Science All Hands Meeting 2003, Nottingham, UK, pp.370-373, September 2003. ISBN 1-904425-11-9 Page 96 [Gaiszauskas et al. 2003b] Gaizauskas R, Demetriou G, Artymiuk P, Willett P. "Protein structures and information extraction from biological texts: The PASTA system". Journal of Bioinformatics 2003;19(1):135-143. [Harkema 2005] Harkema, H., Setzer, A., Gaizauskas, R., Hepple, M. Rogers, J., Power, R., "Mining and Modelling Temporal Clinical Data", proc. AHM2005, Nottingham, UK, Sept 2005, pp. 259 - 266. [Humphreys 2000] Humphreys K, Demetriou G, Gaizauskas R. "Bioinformatics applications of information extraction from journal articles". Journal of Information Science 2000;26(2):75-85. [Ingram 1995] Ingram D. "GEHR: The Good European Health Record". In: Laires M, Ladeira M, Christensen J, editors. Health in the New Communications Age. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 1995. p. 66-74. [Kalra 2003] Kalra D, Singleton P, Ingram D, Milan J, MacKay J, Detmer D, et al. "Security and confidentiality approach for the Clinical E-Science Framework (CLEF)", In: Second UK E-Science "All Hands Meeting"; 2003; Nottingham, UK; 2003. p.825 - 832. [Kohn 2000] Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. "To err is Human: Building a Safer Health System", Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [Lin 2002] Lin Z, Hewett M, Altman. RB. "Using Binning to Maintain Confidentiality of Medical Data". In: Kohane I, editor. AMIA Fall Symposium 2002; 2002; Austin Texas: Henry Belfus; 2002. p. 454-458. [Murphy 2002] Murphy SN, Chueh HC. "A security architecture for query tools used to access large biomedical databases", In: AMIA Fall Symposium 2002; 2002; Austin Texas: Henry Belfus; 2002. p. 452-456. [Novoty 2004] Novoty, J., Russell, M., Wehrens, O., "GridSphere: An Advanced Portal Framework", EUROMICRO2004, France, Sept 2004. [Power 1998] Power R, Scot D, Evans R. "What you see is what you meant: direct knowledge editing with natural language feedback". In: Proc of the 13th Biennial European Conference on Artificial Intelligence (ECAI-98); 1998: Spring-Verlag; 1998. p. 677-681. [Rector 2001] Rector AL, Johnson PD, Tu S, Wroe C, Rogers J. "Interface of inference models with concept and medical record models". In: Quaglini S, Barahona P, Andreassen S, editors. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine Europe (AIME); 2001; Cascais, Portugal: Springer Verlag; 2001. p. 314-323. [Rector 1995] Rector A, Nowlan W, Kay S, "Foundations for an Electronic Medical Record", Methods of Information in Medicine 1991;30:179-86. [Shahar 1997].Shahar Y. "A framework for knowledge-based temporal abstraction". Artificial Intelligence 1997; 90(1-2):79-133 Page 97 [Swanson 1997] Swanson DR, Smalheiser NR. "An interactive system for finding complementary literatures: a stimulus to scientific discovery". Artificial Intelligence 1997;91:183-203. [Sweeney 2002] Sweeney L. "k-anonymity: a model for protecting privacy". International Journal on Uncertainty, Fuzziness and Knowledge-based Systems 2002;10(5):557-570. [Taira 2002] Taira RK, Bui AAT, Kangarloo H., "Identification of patient name references within medical documents using semantic selectional restrictions", In: Kohane I, editor. Amia Fall Symposium; 2002; Austin Texas: Henry Belfus; 2002. p. 757-761. [UMLS 2004] http://umlsks5.nlm.nih.gov [Zhang 2000] Zhang N, Shi Q, Merabti M. "Anonymous public-key certificates for anonymous and fair document exchange", IEE Proceedings-Communications 2000;147(6):345-350. Page 98 |

|||||||||||||||||