Context-Aware QoS Provision for

Mobile Ad-hoc Network -based

Ambient Intelligent Environments*

F.J. Villanueva, D. Villa, F. Moya, J. Barba, F. Rincón

and J.C. López

(Computer Architecture and Networks Group

School of Computer Science

University of Castilla-La Mancha

Paseo de la Universidad 4 13071 Ciudad Real, Spain

{felixjesus.villanueva,

david.villa, francisco.moya,

jesus.barba, fernando.rincon,

juancarlos.lopez}@uclm.es)

Abstract: Lately, wireless networks have gained acceptance for

home networking. Low cost installation, flexibility and no fixed infrastructures

have made it possible home environments rapidly to adopt this technology.

In this paper we introduce the use of mobile ad-hoc networks (MANETs) for

large in-home environments, such as hospitals, government buildings, office

and industrial buildings, etc. Thus, we define an information gathering

mechanism in order to provide a context aware QoS framework, relaxing some

restrictions that are inherited from traditional ad-hoc networks scenarios

(battlefield, catastrophic disaster, etc.) to better fit the specific characteristics

of this new application field. In particular, we propose an adaptative

QoS architecture oriented to provide context-aware quality of service to

the traffic generated in a smart-building network.

Keywords: Quality of services, Mobile Ad-hoc Networks, Context-Aware

Services

Categories: C.2.0, C.2.1, C.2.2, C.2.4

1 Introduction

Traditionally, in-building networks have fixed infrastructures, either

wired or access point -based when wireless. This makes quite difficult

to adapt the building to the new requirements of a specific new technology

or service. Taking into account that the building lifetime is much longer

than the one of that new technology, we can derive that, in general, current

buildings are poorly designed for the future. For this reason users need

new technologies that are faster and easier to deploy, configure and expand.

Furthermore, new applications (collaborative work, e-learning, preventive

health care, etc.) and paradigms (ubiquitous computing, ambient intelligence,

etc.) need some rethinking about how we design and integrate technology

into our daily environments.

*This research is partly

supported by the Spanish Government (under grant TIN2005-08719) and the

Regional Government of Castilla-La Mancha (under grants PBC-05-0009-1 and

PBI-05-0049)

On the other hand, inside future buildings there will be a lot of heterogeneous

devices from different manufacturers. From a practical point of view, the

design of a common infrastructure is difficult because user requirements

and application scenarios are very different and dynamic. Therefore it

is important to have a flexible technology that allows the integration

and expansion of existent infrastructures.

Recent advances in wireless technologies (Bluetooth [Bluetooth,

04], 802.11 [IEEE, 05], ZigBee [Zigbee,

04], etc.), under the mobile ad-hoc philosophy, have made it possible

to establish wireless infrastructures that can be utilized not only as

temporal networks but like a permanent building infrastructure.

Wireless ad-hoc networks are made up of hosts that communicate with

each other over a wireless channel. The nodes have the ability to connect

each other out of their ranges because intermediate nodes perform routing

tasks.

Mobile ad-hoc networks (MANETs) have a set of characteristics that are

interesting for in-home applications and environments:

- They do not need any fixed infrastructure support.

- The nodes are automatically configured (plug and play philosophy).

- They can be fault tolerant.

- They offer support to mobile devices.

However, general MANET mechanisms assume the worst working conditions

for each node in terms of power, bandwidth, mobility and so on (these restrictions

come from the traditional MANET scenarios such a catastrophic disasters

or battlefields). These conditions, with a very high impact in the quality

of the communications, impose hard restrictions that limit the capabilities

of the different nodes.

But in real networks, the worst conditions do not have to apply equally

to all the nodes. Since the different nodes have in general different capabilities,

we can take advantage of this situation to improve the performance of MANET

protocols and algorithms.

In this paper we propose the application of mobile ad-hoc networks to

large in-building environments and an adaptative QoS framework able to

react according to the dynamic environment information.

The architecture described in this paper is based on a previous work

called SENDA (standing for Services and Networks for Domotic

Applications) devoted to easily integrate networks, protocols and devices

for home applications [Moya, 02]. SENDA middleware

defines a set of simple device interfaces, a hierarchical composition mechanism

for both device objects and event propagation, a set of interfaces for

managing and initializing the network and a set of conventions for easier

development of services.

In SENDA, some key factors were identified regarding the deployment

of networks (data, control and multimedia) in in-building environments.

These factors are flexibility, low cost installation and minimum configuration

requirements. All these factors are present in current mobile ad-hoc networks.

On the other hand, some of the constraints assumed in general ad-hoc

networks are no longer present in large in-building environments. We study

these environments and identify which of their features ad-hoc mechanisms

will benefit from.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section

2 explains some previous work in home area networks and QoS. In section

3 the problem we try to tackle is characterized. Section

4 presents our proposed QoS architecture and in section

5 the prototype we have used to validate this architecture is briefly

described. Finally we draw some conclusions and outline

some future work.

2 Previous Work

Wireless networking is perhaps the most attractive approach for the

home, since it avoids the cost of pulling new wires and the challenges

of using existing wiring [Teger, 02]. Similar affirmation

can be done for large in-home environments.

Traditional wireless infrastructures in buildings are based on the use

of access points. With this approach, an important issue we should consider

is the low fault tolerance of the resulting network. A failure in the base

station makes all nodes within its coverage area not to be able to establish

network connections. This problem is overcome in a MANET-based infrastructure

because its nodes have the capability of finding alternative routes to

connect each other. Another problem is the necessity to provide a wired

infrastructure in all the places in which we need to set up an access point.

This increases the costs and it is not a flexible solution at all.

So far, research in MANETs is mainly focused on the networking aspects.

Although ad-hoc networking has been proposed as a promising approach for

in-building infrastructures (i.e. ad-hoc networking communities [Yang,

03] or networked sensor systems [Schramm, 04])

the research community has not faced yet how the characteristics of these

new environments can affect the ad-hoc mechanisms (QoS, routing...) and,

in general, how to adapt them to in-home applications. However, recent

works show the need of studying real world scenarios [Yang,

03][Meddour, 03] and their influence in the performance

of MANET mechanisms.

On the other hand, previous works in the area of home services (OSGi

[OSGi, 05], HAVi [HAVi, 02],

etc.) try to integrate a lot of heterogeneous technologies without considering

how these technologies will be deployed and how the interaction among technologies

can be improved. These aspects are partially tackled in [Lilakiatsakun,

01]. In this work a method to extend the coverage of Bluetooth networks

for the home is proposed. But the possibility of sharing and integrating

resources in a general infrastructure is still underway. Thus, the independent

networks that coexist within a building (for instance, data, multimedia

and control) are still underused due to their isolation from each other

(i.e. a user cannot have access to a HAVi video streaming from a PDA).

Traditionally, in the QoS literature, the different QoS approaches do

not take into consideration that the network resources need to be managed

according to the actual environment needs, changing those needs dynamically

from time to time. Most of the QoS architectures derivates from either

the IntServ architecture [Braden, 94] (per-flow

end-to-end guarantee), or the Differentiated Service architecture

[Blake, 98] (per-class service differentiation), or

MPLS [Rosen, 01] (Multiprotocol Label Switching).

These approaches were developed for the Internet backbone, field that does

not have the necessity and the possibility to manage context-aware information.

This information is not taken into account and, therefore, in most of

the QoS architectures, the relative priority of the network traffic is

totally dependent of the traffic characteristics (for example, the multimedia

traffic needs low delay, real time traffic needs to be deterministic, etc.).

On the contrary, in a real in-building scenario, it is essential that the

priority of the traffic flow also takes into account the actual status

of the environment.

Lately, policy-based management, introduced by IETF, is a more flexible

approach to the QoS management so it can adapt itself to changing requirements

over a long period of time [Chaouchi, 04]. Again,

this solution has been proposed for Internet and the policies are associated

to the network parameters and the user needs, but they do not take into

account the context information. Policy control schemes for mobile networks

[Zheng, 04] have been also proposed using the same

approach.

The QoS architectures for MANETs proposed so far (FQMM [Xiao,

00], INSIGNIA [Lee, 00], etc..) show the same

problem as well (context unaware), and this fact, together with

the typical restrictions of MANET's traditional application fields (relaxed

in our model as we will see in the next section), make these architectures

inappropriate for our application field.

3 Problem Characterization

In current buildings we find more and more a lot of devices with wireless

capabilities that have different characteristics in terms of mobility,

performance and so forth.

Figure 1 depicts a typical scenario where, taking

into account the above considerations, three types of ad-hoc nodes can

be identified:

- Vertebral nodes: These are nodes with few position changes,

with enough capabilities to perform management tasks and with no power

consumption problems (desktop computers, information points, cash dispensers,

some types of electrical appliances etc.). These nodes are represented

with a black circle in Figure 1

- Auxiliary nodes: We are referring to mobile nodes with still

enough performance to do management tasks (laptop computers, etc.). These

nodes are represented with a dark gray circle in Figure

1.

- Clumsy nodes: These nodes are characterized by their high mobility,

their lower performance and their hard power restrictions (mobile phones,

PDA's, etc.). These nodes are represented with a light gray circle in Figure

1. Clumsy nodes are sinks and sources of information and rarely need

to do management tasks (only when, due to the existence of some faulty

nodes, it is strictly necessary to establish new connections to keep the

network working).

Figure 1: Node classification

According to this classification, it is clear that the management responsibilities

will be assigned first to vertebral nodes, then to auxiliary

nodes and finally, if needed, to clumsy nodes. In this paper we

will consider only QoS tasks, but the same philosophy has been followed

for routing tasks [Villanueva, 05] and would have

to be followed with others, such as service discovery, fault tolerance

and so on.

A restriction imposed by our architecture is the necessity of establishing

a set of nodes (vertebral nodes mainly), which provides a minimum

coverage. This restriction is similar to the current problem with access

point based infrastructures. Nevertheless, in our architecture any of the

nodes (generally vertebral and auxiliary nodes) can play

this role and in the case of failure they can establish alternative paths

through the other nodes (vertebral, auxiliary or even clumsy

nodes).

Other elements that are present in the architecture are gateways

or bridges, which are nodes that offer interconnection capabilities

between devices from different technologies. We can use gateways from third

parties; for example, an IEEE 1394 [IEEE1394, 03]

to wireless 802.11 bridge has been developed by Philips [Philips,

03]. With these types of bridges and with the interfaces defined in

SENDA, we can control HAVi devices (multimedia platform based on an IEEE

1394 network [HAVi, 02] ) with, for example, a simple

PDA with an 802.11 interface.

4 The Context-aware QoS Architecture

Integrated environments with different types of services (with their

associated network traffic) need mechanisms to manage the Quality of Service

(QoS), so as to provide different resources availability depending on their

relative importance. Analyzing the traffic generated by the most typical

applications running in large home environments, four general classes of

traffic can be identified:

- Control traffic.

- Multimedia traffic.

- User traffic.

- Best effort traffic.

Control traffic is composed of commands whose goal is to sense and control

the environment (temperature, presence, etc.). To reach high levels of

interaction between users and environment (that could lead us to an ambient

intelligence approach), the way this type of traffic is considered turns

out to be of special importance.

Multimedia traffic is a type of traffic more and more important in current

in-building services. It has very hard requirements in terms of delay,

bandwidth, etc. This type of traffic includes VoIP applications, security

video streaming, videoconference applications etc.

User traffic is mainly the traffic generated by the most common computer

applications we can find in this kind of environments: database transactions,

collaborative work, etc. Finally, other types of traffic are embedded into

the "best effort" class (web surfing, e-mail and so on).

These types of traffic have distinct requirements (bandwidth, delay,

loss rate, etc.) that need a different amount of resources at network level.

We should emphasize that not at all applications have the same importance

in function of the environment status at a time. For example, the security

video streaming in an office building has more importance (therefore it

needs more networks resources) at night than in the day since in the day

it is suppose that the building has activity (workers, security personal,

clients, etc.).

The granularity of traffic classification could be more specific, for

example, in multimedia traffic we could classify the videoconference traffic

in different way than security video streaming in order to improve the

resources for each traffic flow in each time.

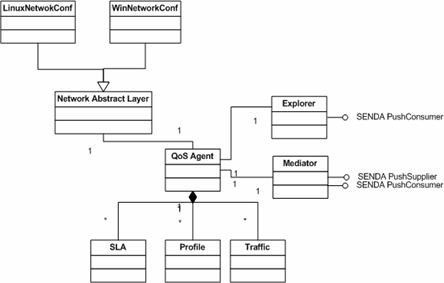

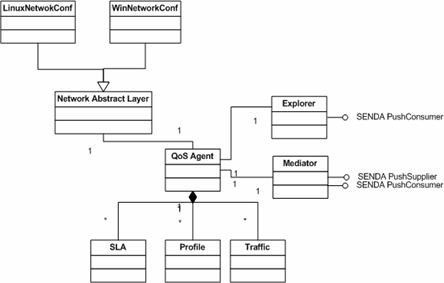

Figure 2: Conceptual model

The way to provide these resources is through QoS agents defined

by our middleware (Figure 2). A QoS agent is

an embedded software component that resides in each node and controls network

resources. To do so, the QoS agent (using a factory pattern) needs to know

the specific operating system that is running on each particular node and

how to interact with it (in our case we have considered just MS Windows

and Linux nodes).

Different types of traffic change their importance and requirements

according to different events (for instance, in an emergency situation)

or periods of time (for instance, at nights). In order to adapt our network

resources to these situations we have defined profiles. Profiles

assign resources to traffic types according to events and/or periods of

time. A profile is a set of rules. Two types of rules are defined:

- Pre-conditions that include event types, time periods, etc. which have

to be satisfied before applying the allocation rules.

- Allocation rules, as, for instance, the bandwidth allocation for each

class of traffic that has been defined.

Profile definitions are shared by all the nodes in the same environment

and only one profile is active at a time. For example, when an event occurs,

the QoS agent checks out whether or not all the preconditions are satisfied

for a given profile. If so, the QoS agent fires the allocation rules that

will modify the network level in agreement with that associated profile.

Profiles, classes of traffic and description of services (which are

local to nodes) are integrated in a SLA (Service Level Agreement),

which is written in XML language (XML is more and more used for network

and services management, offering important advantages [Pras,

04]). The SLA is environment specific and must be known by all

the nodes that belong to that environment. The description of a service

is only local to the node that provides it. The node is responsible for

marking the traffic it generates. Each packet gets its TOS (Type of

Service) IP field marked according to the Differentiated Service

philosophy. Only the clumsy nodes do not need to know this SLA because

they do not perform administrative tasks. Since Differentiated Service

terminology point of view, our vertebral and auxiliary nodes

are the core of the network.

A simplified description of a default profile regarding the bandwidth

for every type of traffic is as follows:

<profile name="usual">

<preconditions>

<timetable>office</timetable>

<alarms>false</alarms>

</preconditions>

<class_traffic>

<control><bw>10</bw></control>

<multimedia><bw>40</bw></multimedia>

<user><bw>25</bw></user>

<b_effort><bw>25</bw></b_effort>

</class_traffic>

</profile>

In this example, the profile assigns 10, 40, 25 and 25 percent of the

total bandwidth to control, multimedia, user and best effort traffic, respectively.

The network layer is abstracted by an API defined in an interface definition

language (in the prototype described below, we have used CORBA IDL [OMG,

04]). This API provides a set of operations that are independent of

the operating system.

QoS agents interact with events and services (in our case, events and

services are managed by the SENDA middleware) through explorers

and mediators. An explorer is able to monitor all the events generated

by the SENDA middleware and communicate them to the QoS agent. When a new

node is added to a building environment the QoS agent request the environment

profile and the active profile by mean of the explorer entity. All nodes

with QoS responsibilities (vertebral and auxiliary nodes) are synchronized

by means of administrative event channels. In this way, in all nodes the

same profile is active at a time like we mentioned before.

In the other hand, a mediator is a software component that informs services

(SENDA services) of any decision made by the QoS agent based on the network

status. Services, which are able to control their outgoing traffic, have

to adapt themselves to the mediator's indications. For example, an MPEG-4

streaming service can adapt their codec features to the actual state of

the network. When a service is initialized provides throught mediator component

to the QoS agent of its description in order to establish the appropriate

filter at network level.

For example, a typical structure of a service description (similar to

the service level specification in DiffServ terminology) in our SLA is

as follows:

<service name="vigilancestream">

<src>localhost</src>

<protocol>udp</protocol>

<port_src>10095</port_src>

<dest>any</dest>

<dest_port>10095</dest_port>

<traffictype>multimedia</traffictype>

<bandwidth unit="k">100</bandwidth>

<avpkl>100</avpkl>

</service>

The role of the gateways nodes (they are generally vertebral nodes)

is to fulfil the QoS requeriments of the active profile, matching the QoS

parameters of the different network technologies available at every side

of the gateway. In a similar way, they have the responsibility of marking

the traffic from one network to another. For example, all traffic coming

from Lonworks devices (non-IP traffic) that goes to a WiFi environment

has to be marked with the 'control traffic' code.

At the MAC layer, similar considerations can be made so as to improve

the QoS making the gateway to match, at this level, the QoS parameters

from the different technologies considered by the gateway. So far our architecture

does not define a QoS model at the MAC layer, since the variety of technologies

would make it necessary a particular model for each one. An example that

covers all the layers for WiFi technology is shown in [Chen,

04].

Finally, QoS provisioning in ad hoc networks is not focused on any specific

layer, since it rather requires coordinated efforts from all layers [Sesay,

04]. In this sense, we also have developed a modification of the AODV

routing algorithm [Perkins, 03] in order to improve

the performance using the vertebral nodes as a backbone of the network.

In this way, our approach shows more reliable paths decreasing of number

of lost packets. A complete description of this algorithm is shown in [Villanueva,

05].

5 Prototype

As we mentioned before, the proposed architecture is based on a previous

work called SENDA. SENDA was initially designed having in mind the main

problems that arise when you want to facilitate the deployment of services

at home: the integration of networks, protocols and devices and the design

and management of the services themselves. In this sense, the SENDA middleware

is the key part of the architecture.

Afterward, the use of mobile ad-hoc networks as the basic infrastructure

for in-home networks, based on the capabilities described along this paper,

came up as one of the most important goals. Thus, the SENDA prototype was

extended to include the MANET approach described in this paper.

Two wireless ad-hoc gateways for the two most relevant home technologies

(X10 and Lonworks) have been developed:

- An X10 to 802.11 gateway implemented in a TINI (Dallas Semiconductor)

device [TINI, 05]. In order to allow us to perform

the routing tasks, a Java version of the AODV algorithm has been developed.

For the QoS framework, the TINI device mark the TOS field of a IP packet

with the control code if in this IP packet there is information about X10

devices.

- The Domobox@ gateway (developed in collaboration with Telefónica,

the Spanish telephone company) [Villanueva, 00].

This device is a low cost interface to X10 and Lonworks technologies easily

controlled through the TV remote control. Besides the Ethernet and the

GPRS (General Packet Radio System) interfaces, an 802.11 version was developed

so as to make of it a vertebral node in our prototype.

Figure 3: Simplified UML diagram of the QoS architecture

Figure 3 shows the UML diagram of the architecture

that has been implemented in each vertebral and auxiliary node. Auxiliary

nodes are laptops and clumsy nodes are PDAs and wireless devices

with PIC processors [PIC, 03] . These wireless devices

are used to control simple home appliances connected to the SENDA prototype.

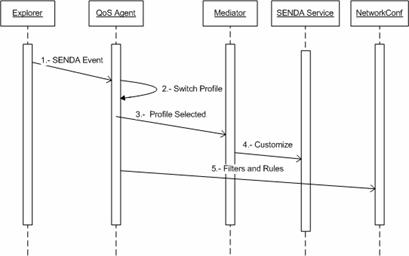

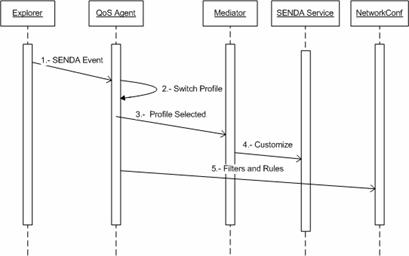

Figure 4: A switch profile sequence diagram

The sequence of messages managed by the QoS framework in order to switch

from a profile to another is shown in the Figure

4. The Explorer entity sends all relevant SENDA events to the

QoS Agent (message 1 in figure 4), then the

QoS agent check whether the received event involves a switch of

the actual profile (message 2 in figure 4) to another

previously defined. If it is necessary to change the active profile, the

QoS agent notifies the new selected profile to the Mediator

object (message 3) and this Mediator object notifies the necessary commands

for customize its behaviour for the new profile to all SENDA services.

Additionally, the QoS Agent will configure the network layer through

a NetworkConf object specifying the rules and filter defined within

the new selected profile (message 5).

The vertebral nodes are desktop computers with 802.11b extensions

running GNU/Linux. For example, for the vigilance streaming service

shown above, the QoS agent of this node has to mark all packets that

this service originates. With the above specification, and

considering a GNU/Linux platform, the next rule is created in

iptables (administration line command tool for the network

layer):

Iptables -t mangle -I OUTPUT -p udp -m udp -sport 10095 -dport 10095

-s localhost -j TOS -set-tos 16

With this rule, all IP packets generated by this service will be marked

with the multimedia code. In a similar way, the forwarding rules for different

types of traffic are established according with the profile that is active

at every moment.

In the Table 1, the TOS value for each type of traffic

is shown.

| TOS value |

Expected behaviour |

Traffic type |

| 16 |

Minimize Delay |

Multimedia |

| 8 |

Maximize throughput |

User Traffic |

| 4 |

Maximize Reliability |

Control |

| 0 |

Normal Service |

Best Effort |

Table 1: TOS values in the prototype

6 Conclusions and future work

Currently, in-building applications use a wide variety of technologies.

User requirements include the need of using heterogeneous devices with

different functionalities and low deployment and maintenance costs. Mobile

ad-hoc networks offer a good solution to these problems as they fulfil

all of these requirements.

In this paper, we have characterized the in-building scenarios so as

to be able to successfully apply mobile ad-hoc networks mechanisms to large

in-building environments. According to the proposed model, we have introduced

a quality of service architecture that takes advantage of the specific

features of those environments to improve the performance of the MANET

based solution. Our architecture provides per-class service differentiation

taking into account context information.

Finally, we have presented the prototype (based on a previous work called

SENDA), where these proposals have been proved.

In the near future, our work is mainly focused on widening the range

of services we can provide based on the SENDA architecture and using the

MANET philosophy. In this sense, other issues related to in-home services

and their applications in this scenario (SENDA and MANETs) should be studied

(for instance, service discovery, fault tolerance, security and so on).

References

[Blake, 98] S. Blake, D. Black, M. Carlson, E. Davies,

Z. Wang and W. Weis. "An architecture for differentiated service".

RFC 2475. Dec. 1998.

[Braden, 94]R. Braden et al., "Integrated Services

in the Internet Architecture An Overview", IETF RFC 1663, June 1994.

[Bluetooth, 04] Bluetooth SIG "Specification

of the Bluetooth System v2.0" Available at http://www.bluetooth.org

November 2004.

[Chaouchi, 04] H. Chaouchi "A new policy-aware

terminal for QoS, AAA and mobility management" International journal

of network management. 14:77-87. 2004.

[Chen, 04] L. Chen and W. Heinzelman, "Network

Architecture to Support QoS in Mobile Ad Hoc Networks" Proceedings

of the International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME '04), June

2004.

[HAVi, 02] HAVi Consortium "HAVi

specification V1.1" Available at www.havi.org. 2002.

[IEEE, 05] IEEE Standards Association http://grouper.ieee.org/groups/802/11/

[IEEE1394, 03] 1394 Trade Association "IEEE

1394 The Home Entertainment Network" Available at http://www.1394ta.org/.

2003

[Lee, 00] S. B. Lee, G. S. Ahn, X. Zhang and A.T.

Campbell "INSIGNIA: An IP-Based Quality of Service Framework for Mobile

Ad-Hoc Networks" J. of Parallel and Distributed Computing, 60:374-406,2000.

[Lilakiatsakun, 01] W. Lilakiatsakun and A. Seneviratne

"Wireless Home Networks based on a Hierarchical Bluetooth Scatternet

Architecture" 9th IEEE International Conference on Networks, Bangkok

(Thailand), Oct.2001.

[Meddour, 03] D.E. Meddour, B. Mathieu, Y. Carlinet

and Gourhant "Requirements and Enabling Architecture for Ad-Hoc Networks

Application Scenarios" Workshop on Mobile Ad Hoc Networking and Computing.

MADNET 2003.

[Moya, 02] F. Moya and J.C. López

"SENDA: an alternative to OSGI for large-scale domotics",

Networks, The Proceedings of the Joint International Conference on

Wireless LANs and Home Networks (ICWLHN 2002) and Networking (ICN

2002), World Scientific Publishing, pp 165-176, Aug. 2002.

[OMG, 04] OMG group, Common Object Request

Broker Architecture: Core Specification. Available at www.omg.org March 2004.

[OSGi, 05] OSGi Alliance. "OSGi Service

Platform, Release 4 CORE" Available at http://www.osgi.org

October

2005.

[Perkins, 03] C. Perkins, E. Belding-Royer and S.

Das "Ad hoc On-Demand Distance Vector (AODV) Routing" RFC 3561.

Jul. 2003.

[Philips, 03] New available on line at http://www.semiconductors.philips.com/news/publications/content/file_1024.html

[PIC, 03] Microchip "PIC16F87XA Data

Sheet" Available at www.microchip.com

[Pras, 04] A. Pras, J. Schönwälder, O.

Festor, "XML-Based Management of Networks and Services", Guest

Editorial, IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 42, n.7, Jul. 2004.

[Rosen, 01] E. Rosen, A. Viswanathan and R.Callon

"Multiprotocol Label Switching Architecture" RFC 3031.January

2001.

[Schramm, 04] P. Schramm, E. Naroska, P. Resch,

J .Platte, H. Linde, G. Stromberg and T. Sturm "A Service Gateway

for Networked Sensor Systems" Pervasive computing. January-March 2004.

[Sesay, 04] S. Sesay, Z. Yang and J. He, "A

survey on Mobile Ad Hoc Wireless Network" Information Technology Journal

168-175. ISSN 1682-6027.2004

[Villanueva, 00] F. Villanueva, F. Moya and J.C.

López, "The Domobox@ Manual Reference", Technical Report

SENDA-UCLM/06-2000, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Oct. 2000.

[Villanueva, 05] F.J. Villanueva, J. de la

Morena, J. Barba, F. Moya and J.C. López "Mobile Ad-hoc

Networks for Large In-Building Environments" accepted in

Wirelesscom. Hawai. USA. June 2005.

[Teger, 02] S. Teger and D. J. Waks

"End-User Perspectives on Home Networking" IEEE

Communications magazine. Apr. 2002.

[TINI, 05] http://www.ibutton.com/TINI/

[Xiao, 00] Xiao H., .Seah K.G., Lo A. and Chua

K.C. 2000 "A flexible quality of service model for mobile

ad-hoc networks". IEEE VTC2000-spring, Tokyo. May 2000.

[Yang, 03] L. Yang, S. Conner, X. Guo,

M. Hazra, J. Zhu "Common Wireless Ad Hoc Network Usage

Scenarios". IRTF ANS Research Group. Internet Draft. Work in

Progress. Oct. 2003.

[Zheng, 04] H. Zheng and M. greis

"Ongoing research on QoS Policy Control Schemes in Mobile

Networks" Mobile Networks and Applications 9, 235.241,

2004.

[Zigbee, 04] Zigbee Alliance, "Zigbee

Specification", available at www.zigbee.org, December 2004.

|